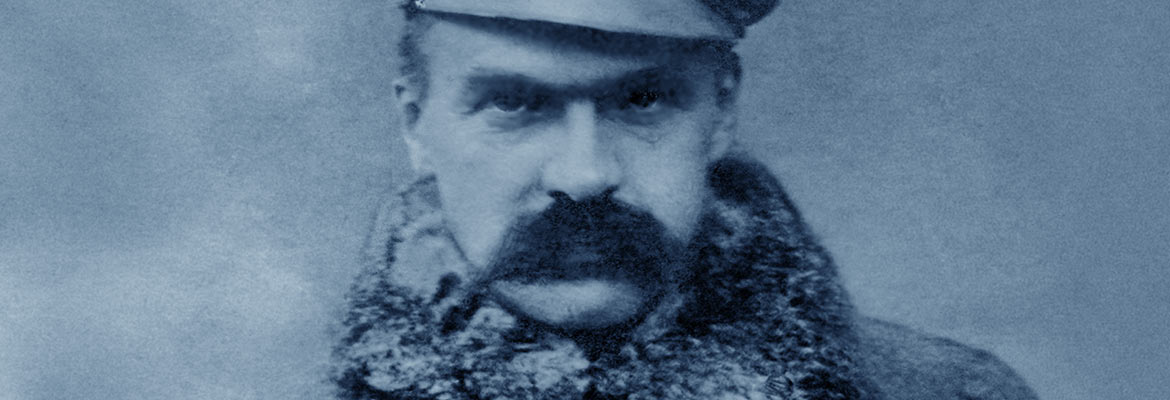

Józef Piłsudski 1867–1935

ZIUK

Józef Piłsudski was born on December 5, 1867, in Zułów, the Vilnius region, in the lands of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania, under the Russian partition. He grew up in the patriotic atmosphere of his family home. The greatest influence on the formation of Ziuk’s personality – that’s how Józef was called in the family – was his mother, Maria née Billewicz. Owing to her, Piłsudski began keen on Polish history and literature, especially romantic literature. He also took over from his mother the basic values of personal dignity, courage, honesty, honor and, above all, the pursuit of the freedom of the homeland. Piłsudski was greatly influenced by the legend of the January Uprising, especially the secret National Government. Józef Wincenty Piłsudski – Józef’s father – was the commissioner of the government in the Samogitia region.

The idyllic years spent in Zułów, however, marred by the memory of the defeat of the uprising, were interrupted in 1875 by a fire at the manor and estate. After this disaster, the Piłsudski family moved to Vilinius. Its material status clearly deteriorated.

While attending high school in Vilnius, Ziuk encountered brutal Russification. At that time he was, along with his brother, Bronisław, one of the co-founders of the patriotic and self-teaching student organization – “Spójnia.” After high school graduation, he studied medicine in Kharkov for a year. In 1887 he was administratively exiled to Siberia for five years for helping Russian revolutionaries preparing an assassination attempt on the Tsar. He was involved in it by his brother Bronisław, who was associated with the conspirators. During the trial of the would-be assassins, Bronisław Piłsudski was sentenced to death, but the sentence was changed to several years’ exile in Siberia.

Józef Piłsudski’s stay in Siberia, in Kireansk and Tunka, during which he met with independence activists, veterans of the January Uprising, Polish and Russian revolutionaries, greatly affected the formation of his views. In Siberia he experienced his first youthful love, but the feeling did not stand the test of time.

WIKTOR

After returning from exile in 1892 to Vilnius, Piłsudski became active in the Polish Socialist Party (PPS). Among its main goals, the struggle for an independent Poland was combined with the need for deep social reforms. Piłsudski adopted the pseudonym “Wiktor.” He quickly became one of the party’s leading activists and became part of its leadership. He was also a publicist and editor-in-chief and publisher of “Robotnik.” In 1899 he married Maria Juszkiewicz née Koplewska, who was affiliated with the PPS. A year later, he was arrested with her in an apartment in Łódź, where there was a secret PPS printing house. The escape from the Warsaw Citadel was impossible, but the party colleagues prepared a plan to free Piłsudski. Simulating mental illness, he was taken to a psychiatric hospital in St. Petersburg. From there, with the help of a Polish doctor, a member of the PPS, he escaped and in 1901 made his way to Galicia – from then on it became the base of his activities, which took on an increasingly pro-independence character.

In 1904, Piłsudski, wishing to take advantage of the Russo-Japanese war to carry the Polish cause internationally, traveled to Tokyo and submitted a memorandum proposing cooperation between the Japanese authorities and the PPS. At that time he met with Roman Dmowski, who had also come to Tokyo and intended to thwart these plans.

In 1905-1906, Józef Piłsudski headed the Combat Department of the PPS. While inspecting one of the arms depots, he met Aleksandra Szczerbińska, with whom he had a long-term relationship that ended in marriage.

Piłsudski was against individual terror and the use of militias for ad hoc activities. He believed that it was necessary to lay the groundwork for the creation of an army in the future, which would be able to take up the fight for Polish independence under favorable conditions, and that a general strike could be transformed into a national uprising. Against the background of attitudes toward Polish independence and the Russian Revolution, a split occurred in the PPS in 1906. The so-called “youngsters” who began to dominate the party rejected the idea of Polish independence enshrined in the PPS Paris program of 1892, associating themselves with the Russian revolutionary movement and seeing the future of Poles in a socialist, federalist Russia. Piłsudski and his partisans, called “the old ones,” formed the pro-independence PPS-Revolutionary Faction. Most of the PPS fighters sided with Piłsudski. The symbolic end of the PPS Combat Organization was the operation at Bezdany in 1908, led by Piłsudski. It brought funds to undertake military-independence activities – an idea to which he devoted himself in the following years. He wanted to break the passivity of the vast majority of Poles, who had stopped thinking about fighting for independence with arms in hand.

COMMANDANT

Inspired by Józef Piłsudski, the clandestine Union of Active Struggle (ZWC) was formed in Lviv in 1908, founded by Kazimierz Sosnkowski. Overt emanations of the ZWC were the organizations formed in 1910-1911 – the Riflemen’s Association and the Riflemen. Their goal was to create cadres for the Polish Army. The Provisional Commission of the Confederated Independence Parties, established in 1912, appointed Piłsudski as the Commander-in-Chief of the Polish Armed Forces, which also included the Polish Riflemen’s Squads, founded on the initiative of independence-minded national youth, and later also the Podhale and Bartosz Squads. The title “Commandant (Komendant)” has since become permanently associated with Piłsudski’s name.

On August 6, 1914, the First Cadre Company, created by Józef Piłsudski from members of the Riflemen’s Association, Rifleman and Polish Rifleman Squads, set out from Kraków’s Oleandrów to the lands under the Russian partition. Piłsudski’s soldiers were to launch an anti-Russian uprising in the Kingdom of Poland (Congress Kingdom of Poland). The failure of these plans, in view of the lack of mass support by the Congress Kingdom’s population, as well as the Austrians’ opposition to Piłsudski’s independent activity – creating a Polish administration – caused him to decide to incorporate his Riflemen’s Troops into the Polish Legions. He was losing his independence, but gaining the opportunity to continue pro-independence work.

The Polish Legions were formed on the initiative of Galician politicians, in consultation with Vienna. In August 1914, they established the Supreme National Committee, which was the political patron of the Legions. Piłsudski became commander of the 1st Infantry Regiment and then the 1st Brigade and gave it an independence drive. He gained great authority in the ranks of the brigade and devoted followers. The 1st Brigade took part in many battles, and the heaviest was fought under the Commandant’s lead at Kostiuchnówka in Volhynia in July 1916. The soldiers of Piłsudski’s brigade were distinguished, like those of the other two brigades, by their tenacity and determination in battles.

On November 5, 1916, the Kingdom of Poland was established on the initiative of the Austro-Hungarian and German emperors. It was a dependent state creation, but the fact of its existence made the Polish question an international issue. Piłsudski thought it was worthwhile to get involved in view of this, and took over the leadership of the Military Commission of the Provisional Council of State.

After the February Revolution in 1917 in Russia, he came to the conclusion that Russia was no longer the greatest danger to Poland’s cause of independence; instead, it was Germany and Austria-Hungary, occupying Polish lands. He broke with the central states in the summer of 1917, triggering the so-called Oath Crisis. It resulted in the detention of most of the legionnaires and Piłsudski’s imprisonment by the Germans in the Magdeburg fortress.

CHIEF OF STATE

Józef Piłsudski returned to Warsaw on November 10, 1918. He was surrounded by the legend of the Siberian exile, the commander of the First Brigade who stood against the Austrians and a prisoner of the Germans. On November 11, the Regency Council put Piłsudski in charge of the army, and a few days later entrusted him with the task of forming a National Government. The most important matter that Piłsudski took up was the formation of the Polish Army, the guarantor of winning and maintaining independence. The soldiers of the Polish Armed Forces – the army of the Kingdom of Poland – were joined by members of the Polish Military Organization mobilized by Piłsudski, recent soldiers of the Legions, Polish Corps in Russia and other volunteers. This is how the core of the Polish Army was formed.

Unable to bring about a government representing the major political forces, Piłsudski appointed the government of Jędrzej Moraczewski, made up of the parties of the independence left. This government established the foundations of a democratic republic. It also introduced social legislation, implementing in large part the PPS’s Paris program. Thanks to this, the danger of Bolshevism in Poland was averted.

Piłsudski, as Provisional Chief of State, ordered elections to the Constituent Assembly. The elections were held in January 1919. Deputies unanimously entrusted Piłsudski with the position of the Chief of State.

Józef Piłsudski was a proponent of the federation concept of cooperation and alliance with Lithuanians, Belarusians and Ukrainians, against Russia, regardless of whether it was “white” or “red.” This is because he believed that any Russia was imperialist. An expression of the federalist concept was Piłsudski’s proclamation “To the inhabitants of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania” (1919) and his alliance with Symon Petlura, leader of the Ukrainian People’s Republic (1920).

The Russian Communists attempted to bring the flame of revolution to all of Europe by force of arms. The road to it led through Poland. In late 1918 and early 1919, Bolshevik Russia undertook a march westward, toward the lands of the Republic. It culminated in the spring and summer of 1920. In April, the Polish Army and allied Ukrainian troops, launched the Kyiv offensive. Its goal was to eliminate the Bolshevik occupation and create the conditions for the establishment of an independent Ukrainian state allied with Poland against Russia.

However, there was not enough time for this, as there was a fundamental turn in the war effort. The Red Army launched a counter-offensive, reaching the outskirts of Warsaw. The Bolshevik Russian invasion was repulsed thanks to a bold strategic plan developed and implemented by Józef Piłsudski, which brought victory in the Battle of Warsaw, in August 1920, and later in the Battle of Neman.

In 1921, delegates from Poland, Russia and the puppet Soviet Ukraine signed a peace treaty in Riga. It established Poland’s eastern border, but at the same time meant the cancellation of the federation idea and the chance for an independent Ukraine. After victory in the war against Bolshevik Russia, Piłsudski was given the marshal’s baton.

Contrary to views that still persist today, Piłsudski did not look only to the east. Although he knew that the question of the western borders would be decided by the Entente, he did not intend to be passive and strongly, albeit secretly, supported the Greater Poland and Silesia insurgents, directing Polish Army officers to Greater Poland and Silesia and providing material aid.

Piłsudski held the position of the Chief of State until December 1922. Presidential elections were then held. He did not run as a candidate. The assassination of the first president, Gabriel Narutowicz, by a nationalist fanatic, was a shock to Piłsudski and influenced the brutalization of his attitude toward political opponents. Not insignificant in this transformation was also the fact that he was a target of numerous slanders and insinuations.

Until mid-1923, the Marshal served as the chairman of the Supreme War Council. He resigned when the “Chjeno-Piast” government was established – in which the National Democrats, who were accused of being morally responsible for the assassination of Narutowicz, played a leading role – and withdrew from political life.

SULEJÓWEK

In 1923, Piłsudski, along with his wife Aleksandra (married two years earlier after Maria’s death) and daughters Wanda and Jadwiga, moved into a mansion built for him in Sulejówek. It was a gift from soldiers to their leader. From then on he divided his time between his family and work as a writer and lecturer. In Sulejówek he wrote a number of articles and works, including “The Year 1920.” At the same time, he observed the political scene and the international situation. He believed that the government in Poland was unstable and the state system was malfunctioning, being a travesty of democracy. He saw that Poland’s position in Europe was deteriorating, due to the agreements between revanchist Germany and Soviet Russia. This alliance threatened Poland’s independence and its borders. Such sentiments were shared by a large part of society.

On May 10, 1926, the “Chjeno-Piast” government was formed, headed by Wincenty Witos. Piłsudski held the politicians of this grouping, mainly from the national right, morally responsible for the assassination of President Narutowicz, as well as for the dramatic, bloody events of the autumn of 1923. The formation of this government became the impetus for the Marshal to stage an armed demonstration to bring about the resignation of the government. The demonstration turned – unfortunately – on May 12, 1926 in Warsaw, into a three-day struggle between soldiers who sided with Piłsudski and soldiers loyal to President Stanislaw Wojciechowski and the Constitution. Wanting to prevent civil war and destabilization of the state, President Wojciechowski and Prime Minister Witos resigned their posts.

MARSHAL

A sort of legalization of the May coup was the election of Józef Piłsudski as the President by the National Assembly. However, the Marshal did not accept the election, and the position of the head of state was assumed by Professor Ignacy Moscicki, who was proposed by him.

In each of the governments appointed since May 1926, Piłsudski was the Minister of Military Affairs. He was also the Inspector General of the Armed Forces, and placed great importance on strengthening Poland’s defense forces. His position in the state went very far beyond his role in these positions. He was mainly concerned with foreign policy and military affairs, crucial to Poland’s independence.

The Marshal entrusted economic matters to his associates. The great achievements of the years after the May Coup were the acceleration of the construction of the port in Gdynia, the construction of the Central Industrial District, the development of the armaments industry and the railroad infrastructure, which was of great importance for the defense of Poland. In 1930, Piłsudski ordered the army to put down a Ukrainian terrorist rebellion in the southeastern voivodeships of Poland.

In the first half of the 1930s, Poland struggled with the economic crisis that swept across the world. The government tried to counteract the effects of the crisis, but was often criticized for being too conservative in its policies.

Faced with an uncertain alliance with France and doubts about what Paris would do in the event of a conflict with Germany, as well as the weakness of the League of Nations, Piłsudski led Poland to sign a non-aggression (non-violence) pact with the Soviet Union (1932) and Germany (1934). However, the Marshal warned his colleagues that the state of peace would not last long.

After the May Coup, there was a growing conflict in domestic politics between the ruling Piłsudski camp and a consensus of centrist and leftist parties (Centrolew), seeking to overthrow the authoritarian rule embodied by Piłsudski. The opposition did not rule out bringing about a change of power through mass demonstrations, riots and strikes. In Piłsudski’s opinion, the Centrolew’s actions and plans threatened to escalate the conflict with consequences dangerous to state stability. Therefore, he decided in 1930 to take an extremely controversial step. He ordered the arrest of some opposition leaders and imprisoned them in the fortress in Brest, where they were brutally treated. Subsequently, the Sanation (Sanacja) authorities brought them to trial with convictions that were, however, quite lenient. Controversy also arose in 1934 when – after the assassination of Bronisław Pieracki, the deputy prime minister and interior minister, by a Ukrainian nationalist – the Bereza Kartuska detention camp was created. Bereza inmates were treated much worse than in prisons. The vast majority of those sent to the camp were communists, enemies of Poland’s independence, subordinate to Moscow, and Ukrainian nationalists, who threatened the territorial integrity of the Republic and used terror.

One of the Marshal’s chief demands was the reform of the state system, which included a fundamental strengthening of the role of the president (based on the American model) while reducing the role of parliament. The new constitution, introducing a presidential system, was passed in April 1935. It played an important role in preserving the continuity of state power after the outbreak of World War II.

Józef Piłsudski passed away on May 12, 1935 at the Belvedere. His passing covered Poland with mourning. For it marked a death of a man who enjoyed enormous respect and authority among the broad masses of Polish society, even among his political opponents. The Marshal was laid to rest in the crypt of the Wawel Cathedral, and as President Ignacy Moscicki said during the funeral ceremony – “To the royal shadows has come a companion of eternal sleep…”.

The legend of Józef Piłsudski, the commander of the First Brigade, the victorious Commander-in-Chief in the war against Bolshevik Russia, the builder of the foundations of the reborn Polish state, survived the times of communist censorship and is still alive today.